Not all Filipinos in the United States speak Tagalog or come from Manila. Sixth Street resident Paul Laus, 72, left his mountain home in the lush jungles north of Manila in 1931 to make his way to America.

Born into a remote mountain tribe called the

Igorats (sic), Laus considers himself an outsider among the mostly Tagalog-speaking Filipinos living in San Francisco.

|

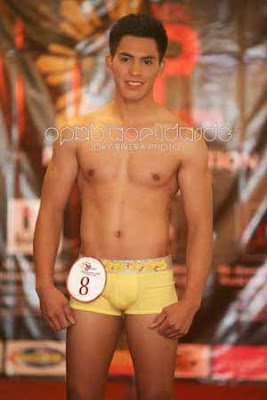

| Paul Laus arrived in the U.S. at age 17, and was 72 when this photo was taken in 1986. He was living on Sixth Street at the time. |

|

He says foreign missionaries and his fellow countrymen viewed his tribe as "ignorant people, illiterate, as compared to the 'civilized Filipinos.' They thought my tribe were non-Christian, wild people, who worship snakes and the sun."

Laus first began to dream of America during the Depression when he was tantalized by tales from fellow classmates returning from study in the United States. When he was told that he would have to wait two years to complete his education while a high school could be built, he resolved to come to America.

To leave home Laus had to bluff his way past the local mayor, governor, and even the "Bureau of Non-Christian Tribes" in Manila, telling them he had everything set up in America, with friends waiting for him.

"I had to tell lies more or less," says Laus. "I was a crazy boy-stubborn, ignorant, disgusted with the Philippines. "

After several months working in Manila, Laus saved enough for his passage to America. Promised not only a job as a houseboy but a chance to go to school by old schoolmates living in America, Laus thought he had it made when he arrived in Toledo, Ohio during the summer of 1931.

But his timing was poor. "A few days before I arrived all of the banks in Ohio closed down," he said. His hoped-for job and school were out.

Nonetheless his friends saw that he ate and had a place to stay and an American businesswoman he had worked for in Manila sent him money.

He used the money to go to upstate New York, where he lived with a priest and his family and worked as a houseboy. He finished high school in just two years and went on to Trinity College in Connecticut on a scholarship.

Loneliness crept in from time to time. An Igorat (sic) boy he'd hoped to hook up with in Connecticut died before Laus got there, because, Laus figures, he couldn't handle the cold.

"If I hadn't lost that friend things would have been good in Connecticut," remembers Laus. "He was an older boy who could have helped me a lot. I wish he would have been alive."

After graduating with a liberal arts degree, Laus struggled to find a job. "I didn't know how to do anything with my hands—I'd been working my head off at Latin!" he says with a chuckle.

When World War II broke out Laus overcame the reluctance of an airplane factory foreman to hire a Filipino when he told him: "Filipinos and Americans are dying together, fighting together. I would like to contribute and do something for the cause."

He worked at the factory until 1944 when he enlisted in the army, joining a special language section.

After a year studying Japanese, Laus was sent to Japan in 1945. The war over at that point, he worked in a prison where he interrogated Japanese soldiers returning home.

Laus has many memories of the people he met in prison—like the pain he felt when he was assigned to visit with five Japanese airmen about to be hanged.

In the early 1950s, Laus taught for several years in the Philippines but returned to America so as not to lose his newly acquired citizenship. He then held various jobs—teaching at American Indian schools in North Dakota and New Mexico, working with Cuban refugees in Miami, washing dishes in Los Angeles.

In the early '60s, Laus moved to San Francisco to work again with the American Indians, helping them find housing and "get acquainted with city life." Funds for that job dried up and he eventually went to work for the Redevelopment Agency, which was then "renewing" the South of Market.

"My job was to tell people about the Redevelopment Agency's plans to get rid of them. It was a hard job. Some old people had lived in the hotels for a long time. That was there they wanted to be, where they wanted to die. I was heartbroken to go into some of those rooms," he remembers.

That position ended when "the agency said our job is done so you're out of work," says Laus. Laus' last job was working in a city psychiatric ward for eight years until 1978 when "I was told I was too old to work."

Once "retired," Laus continued to work anyway, serving on the Board of the Gray Panthers and as chair of Tenants Against Conversion, helping to organize residential hotel tenants.

Perhaps it is Paul Laus' background as a minority in his own country that has fueled his life's work in helping others, from working with American Indians to organizing tenants to counseling condemned Japanese prisoners.

"That's how I've spent my life, says Laus, "listening to people's problems and doing what I could."